Introduction

The Arab Spring in 2011 marked the first major confrontation between authoritarian politics and social media. Social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter were credited with facilitating mass mobilization for pro-democracy uprisings in a hostile political environment. Activists have since made use of social media to increase the cost of repression by publicizing crackdowns, lowering the cost of communicating and coordinating across disparate groups (Zeitzoff 2017; Little 2016; Breuer, Landman and Farquhar 2015), and multiplying the scale and spread of their grievance frames and mobilization calls (Poell and van Dijck 2018; Margetts, et al. 2016). Research on Twitter in particular has highlighted how social media networks facilitate different aspects of contentious mobilization: while users in a peripheral social network position are most effective at recruiting participants, those at the core of the network are more successful at diffusing movement frames and coordinating across disparate networks (Steinert-Threlkeld 2017; Gonzalez-Bailon, et al. 2011).

Today, not only dissidents but also governments have learned how to harness the power of social media to influence public opinion at a scale that was unthinkable before the digital age. In terms of contentious politics, regime leaders have increasingly taken advantage of social media penetration and users’ low digital literacy to monitor, infiltrate, and disrupt social movements (Lynch 2011). For instance, Aday and colleagues provide anecdotes of the dual impact of social media in the case of protests in Iran in 2009. While it facilitated “communication and coordination for those who could not easily meet face to face,” it was also employed by the regime to encourage “government sympathizers to blog and use Twitter and Facebook and other platforms in support of the regime’s position” (Aday, et al. 2010). Similarly, King and colleagues find that in China, government employees pose as ordinary users and fabricate about 500 million social media comments per year to “distract and redirect public attention from discussions or events with collective action potential” (King, Pan and Roberts 2017). More recent studies point to governments’ increasing use of computational propaganda and commercial firms to run bots and inauthentic accounts in order to scale online disinformation campaigns and attack their opposition (Bradshaw, Bailey and Howard 2021).

Despite the many new studies that reveal autocrats’ and dissidents’ emerging digital strategies, there has been less research into how these actors adapt their social media tactics and narratives over time. Particularly, there is a clear gap in the current literature when it comes to assessing regimes’ and challengers’ competing communication strategies and their effects on public dissent in the digital age. Accordingly, recent scholarship has discouraged asking questions about whether social media favors governments or activists and instead focuses on the “strategic interaction and adaptation of new tactics by either side” (Zeitzoff 2017).

We aim to fill this gap in the literature by generating fresh hypotheses, combining insights from political science, sociology, and communication studies, and testing the evolution of social media tactics as part of the dynamics of contentious politics in a repressive regime. We employ a mixed-method design to analyze an original dataset of social media and military media content that has been created since the 2021 coup in Myanmar. Social media will continue to play an important role in shaping Internet users’ experiences in the long run. Therefore, our findings will serve as a solid foundation to guide future scholarship and social media companies on how to facilitate information sharing and communication on social media, which advances the social good without compromising the safety of dissidents or empowering actors with repressive aims.

Our hypotheses

We examine three sets of hypotheses regarding the affordances and limitations of social media for pro-democracy mobilizations and political actors’ corresponding adaptations. First, regarding affordances, unlike conventional mass broadcasting platforms where autocrats can control and censor content, social media platforms’ participatory nature promotes a variety of voices from regime dissidents. We argue this is especially meaningful in repressive regimes with a low level of press freedom, as social media enable pro-democracy activists to discredit authoritarian propaganda, debunk disinformation, and mobilize public support through a venue that is difficult for the government to control. By contrast, the authorities are more likely to focus on projecting an image of regime stability by suppressing reporting on mass protest on the ground. Hence, in such regimes, we expect that social media platforms will feature more resistance-related content than authoritarian media.

H1: Social media platforms are more likely to feature resistance-related content than authoritarian media.

Moreover, analyzing public reactions to social media content allows us to test the deterrent vs. mobilizing effect of anti-protest crackdowns, on which the current literature is yet to reach a widely accepted consensus (Hassan, Mattingly and Nugent 2022). If images of brutal repression are likely to deter further public dissent, fear of digital surveillance by the regime should discourage online users from expressing negative reactions toward crackdown-related posts on public platforms. By contrast, if such images are likely to provoke more defiance against the political elites, the netizens’ outrage should motivate them to dismiss fear of repercussions and publicly condemn repression via negative reactions to crackdown-related content. Following this latter argument, we hypothesize that the emotional content about the repression of protesters is more likely to engender backlash than stifle dissent, making this type of content receive significantly more negative reactions than other types of anti-regime content on social media.

H2: Social media content that broadcasts anti-protest repression is likely to receive more negative reactions than other forms of dissident content.

Nonetheless, social media’s public nature might also limit high-risk anti-regime protests. As repression against dissidents grows over time, activists’ visibility on social media might leave them exposed to surveillance and arrest by an autocratic regime. Hence, we expect anti-regime dissidents will increasingly migrate to private, encrypted messaging platforms to evade crackdowns and discreetly coordinate resistance. By contrast, pro-regime forces are likely to take advantage of this growing vacuum to actively promote their propaganda. Hence, contentious discourses are likely to decrease while pro-regime rhetoric grows on public social media platforms.

H3a: Over time, political content on social media becomes increasingly less contentious.

H3b: Over time, political content on social media becomes increasingly more pro-regime.

To examine our hypotheses, we introduce our case study of contentious politics in post-coup Myanmar.

Post-coup Myanmar

Under General Min Aung Hlaing, the Myanmar military staged a coup against the NLD-led civilian government in February 2021. In response, various resistance groups (e.g., the CRPH/NUG parallel government, CDM government staff, new PDF armed groups, and existing ethnic armed organizations) in urban, rural, and border areas have waged both non-violent and violent campaigns against the military administration (SAC). Ever since, both the SAC and the anti-coup resistance have relied on conventional and digital strategies to discredit each other and gain domestic and international support for their actions.

Military strategies

Based on existing reports regarding military-sponsored content on mass and social media, the SAC has actively deployed public and covert propaganda to manipulate narratives about protesters and frame them as criminals in order to turn public opinion against the resistance movement and in favor of the military.

Public propaganda

In May 2021, military-controlled Myawady TV aired an interview with a monk who claimed that NLD supporters burned down a village and compared the NLD to the Taliban – thereby associating NLD members with criminal images that would resonate with the majority of Bamar-Buddhist audience, many of whom usually discriminate against people of Muslim heritage (Nachemson 2021). Similarly, in June 2021, a military media report accused the NUG and the PDF of “communicating with international terrorists and ARSA [a Rohingya Muslim insurgent group] to grab the State power by force” (Myanmar News Agency 2021). Moreover, the military-controlled Ministry of Information started publishing books that accused the anti-coup movement of being a “revolution to bring back vote-cheaters” (Irrawaddy 2021). The military also disseminated newsletters labeling protests as “riotous situations” and “anarchic mob-like activities and sabotage activities” (Lintner 2021).

Covert disinformation

The SAC has further spread disinformation online under the guise of ordinary observers to craft an echo chamber reinforcing their official propaganda. Numerous reports find military-coordinated trolls have made false accusations and used manipulated images of violence to spread disinformation about anti-coup protesters (Nachemson 2021; Global Witness 2021). According to a report by Fanny Potkin and Wa Lone, “the information combat drive is being coordinated from the capital Naypyidaw by the army’s Public Relations and Information Production Unit, known under the acronym Ka Ka Com, which has hundreds of soldiers there” (Potkin and Wa Lone 2021).

For example, pro-military social media accounts claimed that security forces did not kill protesters but that a third party (e.g., the All Burma Students’ Democratic Front or other protesters) was responsible. Some protesters were even falsely accused of killing the police or raping women. Other pro-military accounts accuse anti-coup activists who have turned to violent methods of being manipulated by foreign forces and Islamist groups like ISIS and the Taliban and even suggest, without evidence, that Muslims were behind the attacks.

Dissident strategies online

The anti-coup forces have similarly taken to social media to condemn the military, highlight its abuses against peaceful protesters, and mobilize the population to participate in resistance activities. Despite the military’s efforts to deter online activism through Internet cuts and social media bans, dissidents continue to find ways to circumvent these barriers, such as through virtual private networks (VPNs) and by relying on communication technologies that do not depend on Internet access.

Resistance through online activism

Facebook and Twitter quickly became organizing tools for resistance against the coup. Almost immediately after the military takeover on 1 February, people amplified the visibility of civil disobedience activities, such as the nightly banging of pots and pans symbolizing resistance (Phyu Phyu Oo 2021), healthcare professionals’ refusal to work in military-operated hospitals (RFA 2021), and traditional resistance performances in rural areas (Jordt, Tharaphi Than and Sue Ye Lin 2021) to coordinate and maximize their impact. Protesters also used social media to broadcast violent crackdowns against peaceful protesters by military forces to generate outrage and motivate greater action both domestically and internationally.

Overcoming digital repression

After the military banned Facebook on the fourth day of the coup, protesters began to download VPNs that allowed them to circumvent the ban and continue their online activities (BBC 2021). As the military ramped up its digital repression, it cut all forms of Internet access at night until 28 April 2021 and restricted all mobile data around the clock starting on 15 March 2021 for more than 50 days (Netblocks 2021). Then, the SAC moved to charge and arrest online users who were found to use VPNs or post dissident content. According to a recent advocacy statement by concerned civil society organizations:

“The amended Broadcasting Law effectively criminalizes any speech deemed impermissible by the military on a wide range of media – including radio, television, audio and video social media posts, and websites – with up to three years’ imprisonment. Meanwhile, the draft Cybersecurity Law provides overbroad censorship and regulatory powers to the authorities – including the Ministry of Defence with its notorious record of committing abuses amounting to serious international crimes – to censor online content, ordering the furnishing of individuals’ personal data from Internet service providers and control online platforms and services through onerous registration and licensing requirements. Not satisfied with the increasing trend of arrests for alleged illegal VPN usage, the draft Cybersecurity Law proposes to penalize VPN usage with up to three years’ imprisonment. […] The junta are conducting stop-searches of individuals’ devices which often result in arrests, detention, and assault, with impunity” (Access Now 2022).

During this period, dissidents had to rely on more covert methods of activism offline or adapted by moving to the “dark web” (Recorded Future 2021). By using a combination of VPNs, foreign SIM cards, and private encrypted messaging apps, such as Signal or Telegram, protesters could continue to both access the web and avoid detection and arrest by the SAC (Chandran 2022). Protesters also downloaded alternative communication technologies (e.g., Bridgefy) that allowed them to communicate via Bluetooth and avoid using the Internet at all. Moreover, local civil society further launched an international advocacy campaign against Telenor’s sale of its Myanmar business to a military-linked Lebanese company, M1 Group (OECD Watch 2021).

In the next section, we present the original Burmese-language media dataset that we collected and will analyze to test our arguments.

Data & methods

Population & sample

As Facebook is by far the most popular social media platform in Myanmar, examining Facebook content allows us to capture the essence of Myanmar social media. By using CrowdTangle, a social media monitoring platform owned by Facebook, we have collected public posts from all Burmese-language pages and groups daily – capped at the 20,000 most viral posts per day – since March 2021. As for military media content, we collected online issues of The Mirror (ကြေးမုံ) and The Light of Myanmar (မြန်မာ့အလင်း), two SAC-run daily newspapers published during the same period.

Our analysis is based on (1) a random sample of 5,200 Facebook posts over 13 weeks between March and May 2021 and (2) a sample of all 708 daily military newspaper articles whose titles appeared on the first page during the same period.

Regarding military media content, the articles are quite evenly distributed between The Mirror (53%) and The Light of Myanmar (47%), with the majority of articles (58%) containing pictures or photos (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Distribution of military newspaper articles’ type and form.

As for social media content, the Facebook posts come from a wide range of pages and groups, including politics, business, entertainment, media, education, and the community. They are evenly distributed between page posts (45%) and group posts (55%). Almost all of the posts (95%) had fewer than 2,000 interactions (including reactions, comments, and shares) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Distribution of Facebook posts’ type and interactions.

Mixed method

To examine our hypotheses, we worked with Myanmar research assistants to identify key pro-military and pro-dissident narratives in our dataset, as well as the prevalence and evolution of each type of narrative across social and military media. First, we manually coded our sample of posts to get a general understanding of the data. Second, we conducted ANOVA and linear regression analyses to determine whether (1) Facebook is more likely to feature resistance-related content than military media, (2) dissident Facebook posts that broadcast repression are more likely to garner negative reactions than other dissident posts, and (3) Facebook posts with dissident content become less prevalent while pro-military posts increase over time.

Analysis and discussion

Predominant discourse: social vs. military media

Figure 3. Proportion of content that is coup-related.

From March to May 2021, military media featured slightly less coup-related content than social media did (Figure 3): 46.5% vs. 51.5%. In particular, the military newspapers underscored two main narratives (Table 1). First, they made accusations and pushed criticisms of the NUG and foreign actors for allegedly manipulating young people and civil servants to carry out violence and abandon their responsibilities to the public. Second, they repeatedly highlighted the military administration’s unsubstantiated commitment to multi-party democracy and free and fair elections while alleging widespread electoral fraud in 2020.

Table 1. A random sample of coup-related military newspaper articles.

| No. | Newspaper | Content | Date |

| 1 | The Light of Myanmar | Social punishment of non-CDM staff, NLD supporters blamed for not understanding democratic values and not respecting people’s individual choices | 3/9 |

| 2 | The Mirror | Dissidents labeled as followers of a cult who cannot see NLD’s electoral fraud; police follow democratic principles by breaking up the riots | 3/20 |

| 3 | The Mirror | A seriously ill patient cannot get help, CDM doctors criticized as unethical | 4/6 |

| 4 | The Mirror | Military takeover legitimized; NUG, independent media, and foreign actors accused of getting innocent youth involved in anarchic mobs | 4/21 |

| 5 | The Mirror | Min Aung Hlaing urges CDM civil servants and medical staff to return to work as soon as possible, says they can hold different political beliefs under democracy | 4/27 |

| 6 | The Light of Myanmar | Myanmar Central Bank announces it will let people open new bank accounts to secure their assets amid the violence and chaos | 4/28 |

| 7 | The Light of Myanmar | SAC grants commander in Mindat township, Chin State, the authority to impose martial law in order to maintain law and order | 5/14 |

| 8 | The Light of Myanmar | Teachers should impart the right knowledge to young students; article indirectly criticizes CDM teachers and student protesters | 5/22 |

| 9 | The Light of Myanmar | Corrected voting results from seven townships in Shan State, released; claims of missing votes, as well as extra votes | 5/24 |

| 10 | The Light of Myanmar | People advised to stay vigilant against false information and support the administration for national development | 5/25 |

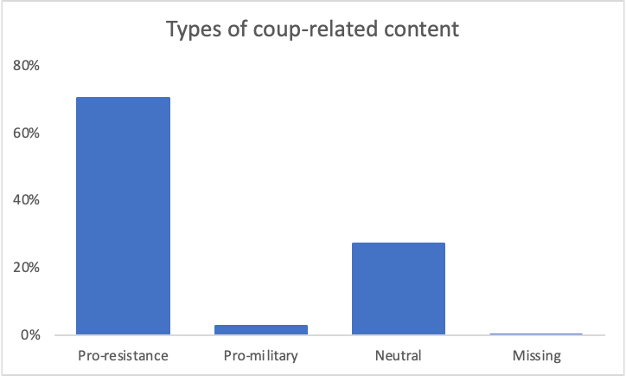

However, in stark contrast to military media, most coup-related Facebook posts (Figure 4) are either explicitly anti-military (70%) or neutral reporting (27%).

Figure 4. Distribution of coup-related Facebook posts.

Moreover, among the Top 10 most viral Facebook posts, 20% of page posts and 70% of group posts are explicitly anti-military, with no pro-military posts (Tables 2, 3). They highlight domestic resistance activities (e.g., NUG, protests, etc.), international advocacy and response (e.g., advocacy at the UN, ASEAN response, military sanctions, etc.), and military crackdowns and activist casualties (e.g., attacks against ethnic armed organizations, militias, and civilians; harassment of CDM participants; etc.). In other words, they condemn the SAC and encourage further resistance.

Table 2. Top 10 viral page posts.

| No. | Content | Date | Interactions |

| 1 | Formation of parallel government | 3/31 | 302,988 |

| 2 | Opposition protest | 3/1 | 131,068 |

| 3 | R2P request to UN | 3/9 | 115,029 |

| 4 | Anti-military content | 3/12 | 107,218 |

| 5 | Malaysia’s three-point proposal to Myanmar | 4/24 | 96,332 |

| 6 | Opposition protest | 5/4 | 89,193 |

| 7 | Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw’s (CRPH) participation in UNSC meeting | 4/9 | 72,231 |

| 8 | Opposition protest mobilization | 4/23 | 70,687 |

| 9 | US & EU sanctions on military | 3/23 | 59,289 |

| 10 | Military attack on ethnic armed organization’s area | 3/27 | 57,281 |

Table 3. Top 10 viral group posts.

| No. | Content | Date | Interactions |

| 1 | Civilian casualties due to military attack in Mindat | 5/15 | 41,827

|

| 2 | Taunting of military’s spokesman | 3/11 | 15,813 |

| 3 | Dr. Sasa’s health | 5/11 | 9,164 |

| 4 | Local support for Myanmar protesters in Korea | 5/2 | 7,332 |

| 5 | Eviction of CDM staff | 5/13 | 7,281 |

| 6 | Death of a front-line student protester | 3/14 | 6,519 |

| 7 | An account of good protest planning | 3/1 | 5,828 |

| 8 | Promotion of a fashion style | 5/12 | 5,499 |

| 9 | Civilian commended for helping someone who had been shot | 3/27 | 5,316 |

| 10 | Turkey’s statement at the UN against the Myanmar military | 3/22 | 5,067 |

In contrast to our affordance hypothesis (H1), we find military media feature more resistance-related content (as a percentage of coup-related content) than social media does (Figure 5). However, the existence of such content on social media is significant as it contrasts with the SAC media’s pro-military discourse.

Figure 5. Proportion of resistance-related content among coup-related content.

Resistance-related content (Table 4) makes up 64.4% of the coup-related military newspaper articles in our sample. These articles repeatedly blame the NUG and foreign actors for orchestrating violent protests, anti-military disinformation, and the destruction of public property to further their own interests. In addition, such posts either highlight unfounded accusations of armed protesters killing each other or criticize anti-coup activists for disrespecting and intimidating pro-SAC supporters.

Table 4. A random sample of resistance-related & coup-related military newspaper articles.

| No. | Newspaper | Content | Date |

| 1 | The Light of Myanmar | Min Aung Hlaing’s speech about violent protesters armed with weapons, in which he justifies the arrests and blames NUG supporters for the protesters’ casualties | 3/9 |

| 2 | The Light of Myanmar | Min Aung Hlaing accuses NUG and foreign actors of manipulating protesters to organize violent riots and attacks on public property and innocent people | 3/21 |

| 3 | The Mirror | Article accuses the US National Endowment for Democracy of funding dissident cells that force medical workers to join the CDM, agitate violence, and spread disinformation against the Myanmar military | 3/29 |

| 4 | The Light of Myanmar | Article discusses Min Aung Hlaing’s wariness of CRPH members and supporters | 4/8 |

| 5 | The Light of Myanmar | SAC shares with a US diplomat how it tries to deal with the NUG’s violent actions in the softest ways | 4/9 |

| 6 | The Mirror | Article accuses NUG of giving false hope to persuade civil servants to join the CDM and advises CDM participants to cooperate with the SAC since most have returned to office | 4/22 |

| 7 | The Light of Myanmar | Dissident politicians accused of manipulating people to carry out violence to further their agenda | 5/5 |

| 8 | The Mirror | Film association urged not to support a particular party but to work for the public good | 5/9 |

| 9 | The Light of Myanmar | NUG accused of destroying peace and stability | 5/12 |

| 10 | The Mirror | Anti-military protesters accused of being unethical and disrespecting others’ ideas and decisions | 5/25 |

By contrast, resistance-related Facebook posts (54.5% of coup-related Facebook posts) are mostly either anti-military (73.3%) or neutral reporting (24.8%) and highlight NUG activities, protests, clashes, casualties, etc. (Table 5). Overall, this contrast between social media vs. military media content further reinforces the notion of military propaganda’s limited ability to dominate public discourse, at least among Myanmar netizens, despite growing repression and censorship.

Table 5. A sample of resistance-related Facebook posts.

| No. | Type | Content | Date |

| 1 | Page | Formation of parallel government | 3/31 |

| 2 | Page | Opposition protest | 3/1 |

| 3 | Page | Opposition protest | 5/4 |

| 4 | Page | CRPH’s participation in UNSC meeting | 4/9 |

| 5 | Page | Mobilization for opposition protest | 4/23 |

| 6 | Page | Strike in Mandalay | 5/5 |

| 7 | Page | Clashes in Kayah State | 5/26 |

| 8 | Page | Emergency call for a hiding place in Mindat township, Chin State | 5/14 |

| 9 | Page | Clashes in Kayah State | 5/24 |

| 10 | Page | Clashes between the PDF and the SAC | 5/23 |

Engagement with dissident discourse

Figure 6 demonstrates the average number of interactions for Facebook posts by different content types. Overall, within our sample, coup-related content received many more interactions on average (1,233) than posts unrelated to the coup (403). Among coup-related posts, neutral (2,289) and anti-military (859) posts received more interaction on average than pro-military posts (357), which is unsurprising given the widespread animosity toward the military among the majority of the Myanmar population.

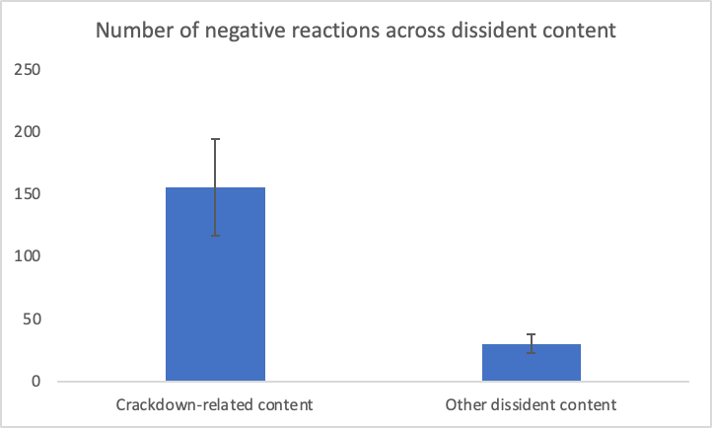

We further hypothesized (H2) that among dissident Facebook posts, those that broadcast crackdowns and arrests by the military against unarmed protesters and civilians will generate more negative reactions (i.e., sad and angry reactions) than those that do not. As expected, we find a significant difference in the average number of negative interactions received by dissident posts that do vs. do not mention military crackdowns: 155 vs. 30 (Figure 7). This finding elucidates how the mobilizing effect of anti-protest repression substantially outweighs its deterrent effect.

Figure 7. Mean number of negative reactions to dissident posts.

Change in social media discourse over time

Our final models evaluate temporal changes in the prevalence of pro-military vs. anti-military posts on Facebook (H3a & H3b). As expected, coup-related posts become increasingly less contentious and more pro-military over time (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Gradual change in the probability of coup-related Facebook posts being anti- vs. pro-military.

The results may reflect asymmetric power differentials and strategic adaptations by the pro- and anti-military forces. Anti-military forces may find it more costly and dangerous to engage in dissident activities on social media due to the constraints on Internet access and fears that engaging online facilitates military targeting of resistance forces. The pro-military forces, by contrast, may feel relatively safer mobilizing online because they feel protected or supported by the military and because the resistance forces have a weaker capacity to retaliate.

Conclusion

Our paper used evidence from post-coup Myanmar in 2021 to examine how autocrats and dissidents adapt political discourse in the digital age. To scrutinize the affordances and limitations of social media for pro-democracy mobilizations, we juxtaposed military newspaper articles with Facebook posts. In contrast to our first hypothesis, we find social media to be less likely to feature resistance-related content than military media. However, we find evidence for a higher rate of negative engagement with crackdown-related content than other dissident content online. Last but not least, although dissident content enjoys a higher rate of engagement on average than pro-military content on Facebook, we find the rate of contentious posts to decrease over time while the number of pro-military posts is growing steadily.

Our findings highlight three main dynamics of contentious politics in post-coup Myanmar. First, our results shed light on the military’s inability to steer public discourse away from increasingly widespread dissident activities. The SAC’s lack of control and legitimacy on the ground has likely made it necessary for the military media to adopt a relatively active reframing of reality to vilify resistance leaders and justify military repression and administration. While military propaganda underscores the consistency in its projected image as championing “disciplined democracy” toward both domestic and international audiences, dissident narratives reveal how the anti-coup resistance appears to be united not because they have a shared ideological goal but because of a shared animosity toward the SAC. This shared animosity and increasing dissent toward the military is further corroborated by our finding that crackdown-related posts receive more negative reactions on average than other dissident content. Finally, a decline in the prevalence of dissident rhetoric on public Facebook pages and groups over time might reflect activists’ increasingly salient risk perception, suggesting the limitations of social media as a dissident tool. Further research involving in-person interviews/surveys or content analysis of encrypted platforms (e.g., Signal and Telegram) is required to triangulate our analysis.

References

“The fluctuations of Italy’s China policy have been attracting attention. The only G7 country to join Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative in 2019, Italy... Read More

“While the BRI MoU did not significantly alter China–Italy relations, the new agreement action plan is unlikely to bring about dramatic changes. The evolution... Read More

“Il porto di Gwadar è una delle infrastrutture principali del corridoio tra la Cina e il Pakistan, che collega lo Xinjiang all’Oceano indiano. Il... Read More

A sedici anni di distanza dalla pubblicazione a Hong Kong, esce finalmente in Italia, nella traduzione dall’originale in lingua cinese di Natalia Francesca... Read More

Le tecnologie quantistiche rappresentano una delle frontiere più avanzate della scienza moderna. Basate sui principi della fisica quantistica, queste tecnologie sfruttano le proprietà delle... Read More

Copyright © 2024. Torino World Affairs Institute All rights reserved