October 27th: a US warship – the USS Lassen – sails within less than 12 nautical miles from Subi Reef and Mischief Reef, in the contested Spratly archipelago, where key players in the region such as China, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan and Vietnam vie for exclusive sovereign- ty. This episode is the most recent sign of growing tensions in the South and East China Seas.

As Beijing attempts to strengthen its position especially in the South China Sea – including through the development of artificial islands – the United States reacts by declaring its commitment to promoting international law and freedom of navigation, and the US Department of Defence stated the trip of the USS Lassen was the first of several scheduled in the coming months.

Empirical proof of growing tensions in the Far East can also be traced in the data on global military expenditure, as presented in the latest edition of the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) Yearbook. The launch of the Yearbook Summary – translated into Italian by T.wai since 2011 – provided the opportunity for an in-depth discussion on security and arms sales in East Asia, jointly organized in Turin on October 28th by T.wai, the University of Torino and the analysts of “Il Caffè Geopolitico”. Dr. Simone Dossi (T.wai and University of Milan), Mr. Marco Giulio Barone (T.wai and Il Caffé Geopolitico) and Prof. Stefano Ruzza (T.wai and University of Torino) examined the key security flashpoints in the region, and the trends of arms sales and acquisitions in East Asia.

The Chinese and US governments have both officially reaffirmed the need to respect protocols and enhance communications trans- parency, in order to avoid misunderstandings or provocations. There are good reasons: several delicate disputes are fuelling in both the East and South China Seas: in the East, the long-running dispute over the Senkaku/ Diaoyu Islands claimed by China but administered by Japan; in the South, the growing tensions about disputed archipela- gos and the construction of artificial islands. Further elements of friction are related to frequent naval standoffs and to the 2013 Chinese decision to create an Air Defence Identification Zone (i.e., an airspace where civil aircrafts have to abide by mandatory identification and localization procedures) covering most of the East China Sea.

In this scenario, Japan’s revision of its security posture – now allowing for further pursuing “collective self-defence”, which can entail the deployment of troops abroad – does not help defuse tensions. What is then the Chinese answer to these dy- namics? It includes both a “stick” and a ”carrot”. On the one hand, China does not disdain shows of force, of which an excellent example is Joint Sea 2015 II, the largest China-Russia drill to date, which took place from August 20th to 28th and included more than 20 vessels from both the Russian Navy and the People’s Libe- ration Army Navy, along with the deployment of advanced equipment. On the other, China’s commitment to economically energize a 21st-century maritime “New Silk Road” does constitute a powerful trust-building initiative on Beijing’s part.

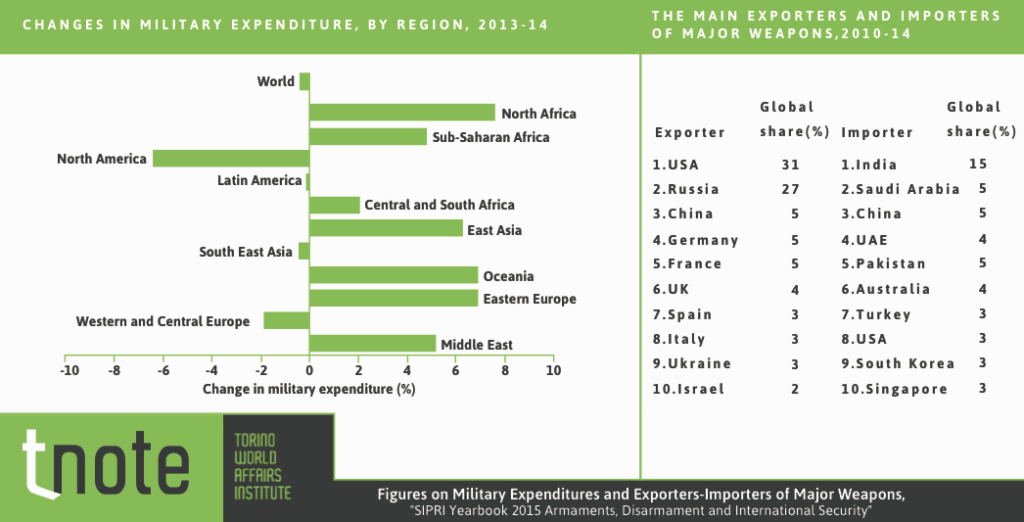

The authoritative data on the international arms trade and arms production contained in SIPRI’s Yearbook help better to frame the situation in quantitative and relative terms. The global volume of arms sales grew by 16% between 2005–09 and 2010–14. Countries in Asia and Oceania received 48% of all imports of major weapons in 2010-14. In the same period, China established itself as one of the top 5 global suppliers, narrowly surpassing Germany and France.

Of the world’s five largest recipients of major weapons, three are located in Asia: China, India and Pakistan. China’s global share of major weapons exports is equivalent to 5%, whereas the Chinese and South Korean global shares of imports account for 5% and 3% respectively.

Global military expenditure in 2014 – approximately USD 1,776 billion – was lower by about 0.4% in real terms compared to 2013. However, this decrease is mostly due to declining purchases in North America and Western and Central Europe, while Asia follows the opposite trend: South Asia and East Asia posted a 2% and 6.2% increase respectively. In the 2014 list of top-10 countries with the highest military spending China ranks second, with 12% of world military expenditure, with Japan and South Korea trailing at 2.6% and 2.1%.

Military spending as a percentage of GDP in these three countries accounts for 2.06% (China), 1% (Japan) and 2.6% (South Korea). SIPRI estimates that in 2014 China’s total military expenditure accounted for nearly USD 216.37 billion (current $), followed by Japan’s 45.78 billion, South Korea’s 36.78 billion and Taiwan’s 10.24 billion. Overall, Central and South Asia combined spent USD 65.9 billion in defence, compared to East Asia’s USD 345 billion – the second-highest spending region after North America. These figures are particularly striking considering there are no major conflicts currently in progress in East Asia, and call for the close monitoring of tensions across the Asia-Pacific region.

T.note n. 3 (November 2015) is authored by Stefano Ruzza and Giorgia Brucato. Stefano Ruzza is Head of Research at T.wai and Assistant Professor at the University of Torino. Giorgia Brucato is Non Resident Research Assistant at T.wai and Analyst at Il Caffè Geopolitico.

Download

Copyright © 2024. Torino World Affairs Institute All rights reserved