Introduction

While the country was still reeling from the impacts of the global coronavirus pandemic, the military coup carried out on 1 February 2021 sent shock waves through Myanmar as people now faced the looming possibility that their democratic era under the National League of Democracy (NLD) would be short-lived. According to the Myanmar Garment Manufacturers Association (MGMA), 55 factories closed temporarily and 13 factories closed permanently in 2021. Garment factory workers, mostly young women, have faced several disruptions because of the coup.

This paper seeks to grasp the impact of the military coup and the COVID-19 pandemic, referred to as the “double crisis,” on the country’s garment sector. The paper is divided into four parts: the first section deconstructs the term ‘double crisis’ to understand the changes in the garment sector from this perspective. The second section is the methodology, which outlines the data used to analyze these changes. The third section presents five different types of changes experienced in the garment factories, namely: (1) changes in export destinations, (2) order cancellations, (3) overtime and wage expenditures, (4) production levels, and (5) the size of the workforce. The fourth section presents the greatest challenges factories have faced in maintaining operations, as well as some perspectives on the future of the garment sector. The conclusion will draw on the key points and arguments made in the paper.

The double crisis

Møller (2022) challenges other researchers using postcolonial critiques of Myanmar to avoid generalizations and instead allow local scholars to offer deeper insights about the situation. In that vein, this paper aims to amplify the voices of the Myanmar people and their experiences. Demonstrating the state of industrial development in the country, primarily through the available data and various sources, requires listening to what the female garment workers, as well as the factory owners, labor unionists, and researchers, have to say about the current events.

In this paper, the term ‘double crisis’ refers to two crises that have gripped Myanmar and had a significant impact on its industrial development. The first crisis is COVID-19, a global pandemic that has gripped the entire world, and the second crisis is the entire period since 1 February 2021. The term has been used by several authors and organizations to illustrate the unique challenges Myanmar is facing. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) reports that under the “twin crises” or “combined crisis” (COVID-19 and military take-over after February 2021), half of Myanmar’s population is projected to be living in poverty by early 2022 (UNDP 2021: 4). The next section will provide more insight into how these crises have impacted the economy, specifically industrial development.

Crisis and industrial development

COVID-19 pandemic

The first crisis that will be analyzed (because it happened first) is the global pandemic. At the end of 2020, the World Bank (2020) estimated that Myanmar’s economic growth for Fiscal Year (FY) 19/20 would decline to 1.7 percent from 6.8 percent the previous year due to COVID-19. Furthermore, the World Bank estimated that the country’s economic growth would remain at 2 percent for the first part of FY20/21. The pandemic is expected to exacerbate the existing inequalities in the country. It was estimated that due to COVID-19, the poverty rate could increase to 27 percent in FY20/21 from 22.4 percent in FY18/19 (World Bank 2021).

The ILO (2020) stated that a global recession was looming because of the pandemic and would gravely affect developing economies already battling a string of inequalities. According to Min Zar Ni Lin and Ngwenya-Tshuma, garment workers in Myanmar suffered an 8 percent loss of net income within six months of the COVID-19 pandemic due to supply chain disruptions and lockdown measures (Min Zar Ni Lin, et al. 2019). From the onset of COVID-19, one of the first challenges that Myanmar’s industrial sectors faced was the disruptions in the supply chains caused by earlier outbreaks in China. For a sector like the garment industry, which relies entirely on raw materials from China, this caused major delays in orders (ILO 2021: 6). Data indicated that imports of the raw materials needed in the garment sector declined 19 percent between 2019 and 2020.[1]

The garment sector faced additional hurdles when some brands canceled or suspended orders from key export destinations due to declining demand. The garment factories in Myanmar reduced 27 percent of their workforce in 2020 to compensate for the loss of cutting, making and packing (CMP) prices from buyers and suppliers (ILO 2021). This has negatively impacted “the profits, wages, job security, and job safety,” (Castañeda-Navarrete, Hauge and López-Gómez 2020). Throughout this process, the vulnerability of (especially female) workers increased immensely as factories laid off their employees to maintain operations, and families who depended on these workers were pushed closer and closer to the brink of poverty.

Political crisis: Military coup

In the case of Myanmar, it is crucial to provide evidence of the factors that have negatively contributed to a decline in the garment sector since the coup. In March 2021, in response to growing civil unrest, the military instituted martial law in some townships, including Hlaing Tha Yar and Shwe Pyi Thar, where a majority of export-oriented garment factories are located. Some reports have suggested that anti-coup protesters mostly targeted Chinese-owned factories in these townships (Lin and Geddie 2021). Factory workers also joined the protests in solidarity with other citizens protesting the military regime. Under this political crisis, tripartite relations (between workers, employers, and government stakeholders) have been strained, as some trade union leaders have been arrested, and further escalation led to some trade unions being disbanded by the military and considered illegal (Donovon and Maung Moe 2021). Many garment workers have lost a significant degree of the rights they had secured before the coup (Min Zar Ni Lin and Ngwenya-Tshuma 2021b). In December 2021, Action, Collaboration, Transformation (ACT) decided to stop its operations in Myanmar because one of its members, IndustriALL, had a local trade union affiliate that could “no longer operate freely” (Glover 2021).

All these events indicate how COVID-19 and political instability have simultaneously disrupted operations of factories, risked the integrity of the sector, and resulted in job losses. This study does not seek to value one crisis over the other but instead illustrates how both have had a critical impact on Myanmar’s garment sector trajectory.

Methodology and limitations

This study was made possible thanks to data obtained from the Foreign Trade Association of German Retailers (AVE) that was collected by the second author of this study in October 2021 under a twinning project between the AVE and the MGMA (see AVE and MGMA 2021). The sampling for the quantitative survey was based on the active garment factories list as of September 2021 provided by the MGMA.

Out of 494 active export-oriented factories, 438 factories in the Yangon region were selected: 324 foreign-owned factories and 114 Myanmar-owned and joint-venture (JV) factories (Lin and Geddie 2021). A stratified random sampling method was employed in the data collection process to select 49 factories: 37 foreign-owned and 12 Myanmar- and JV-owned. Additionally, six in-depth qualitative interviews were conducted with employers, unions, and non-union workers to understand their experiences. Any factory-level data referred to in this paper is taken from the data collected by the AVE, unless otherwise stated.

The survey data of the AVE was only collected in the Yangon region. Owing to travel restrictions and security reasons, no data was collected from export-oriented garment factories outside the Yangon region. This means the data only represents the situation in the Yangon region and does not entirely reflect the entire garment sector environment across the country. According to the MGMA’s active factories list, as of September 2021, 89 percent of garment factories are located in the Yangon region.

Changes brought about by the double crisis

This section explores four areas that demonstrate the changes the garment sector has experienced due to the double crisis, including (1) changes in export destinations, (2) order cancellations, (3) overtime and wages expenditures, (4) production levels, and (5) the size of the workforce.

Changes to Myanmar’s garment export market

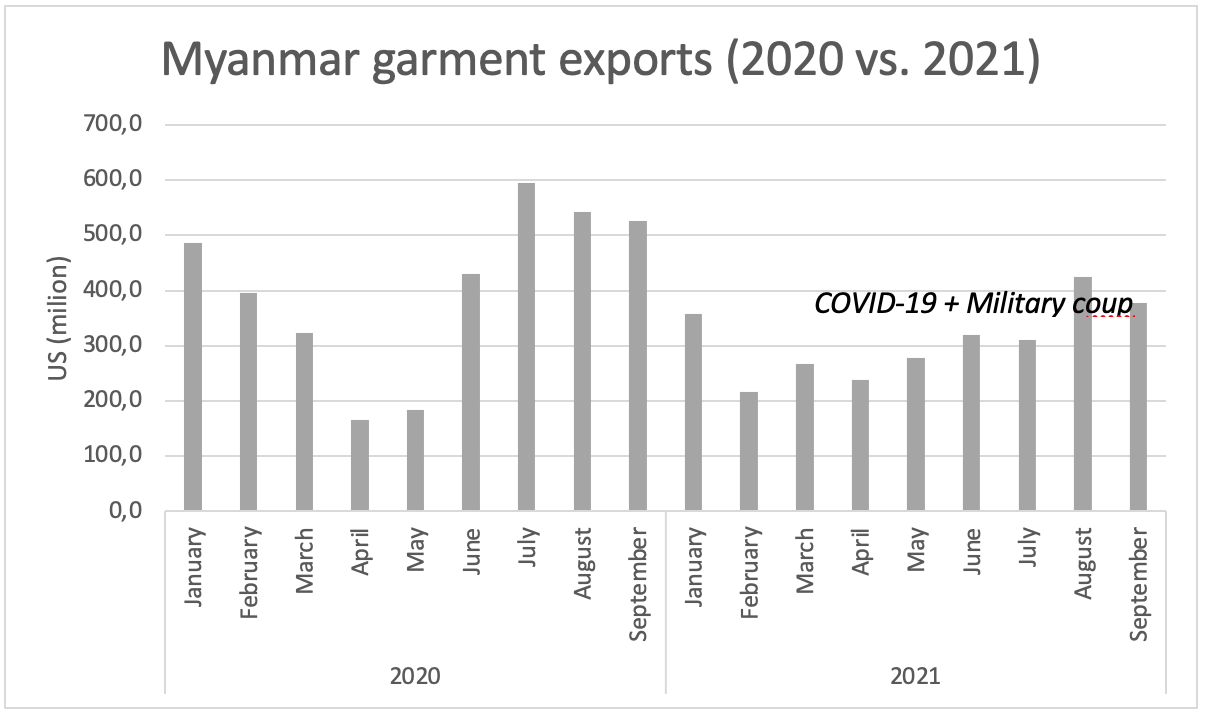

The Central Statistical Organization of Myanmar has reported that the total garment export value of the country in 2021 (January–September) declined by 31 percent year on year, as shown in Figure 1. The pattern shown in the decline of the value of garment exports is consistent with the double crisis narrative. As shown in Figure 1, the lowest levels of export value were in February 2021, when the coup took place. For the rest of 2021, it is evident that the levels remained lower than those in 2020. Based on the level of garment exports, it can be argued that the political instability created by the military coup has had a greater impact on garment exports than the pandemic. The political crisis in 2021 likely compounded the severity of the existing situation.

Figure 1. Value of Myanmar garment exports.

Source: Central Statistical Organization Myanmar.

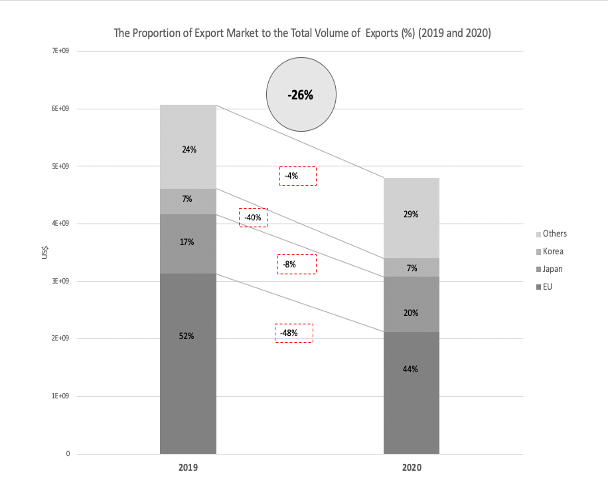

The garment export market is significant because it illustrates Myanmar’s key destination markets. Economic shocks produced by COVID-19 and the military coup have had an impact on the volume of exports and the market destinations. As shown in Figure 2a, UN ComTrade data shows the volume of garment exports between 2019 and 2020 experienced an overall decline of more than a quarter (-26%).

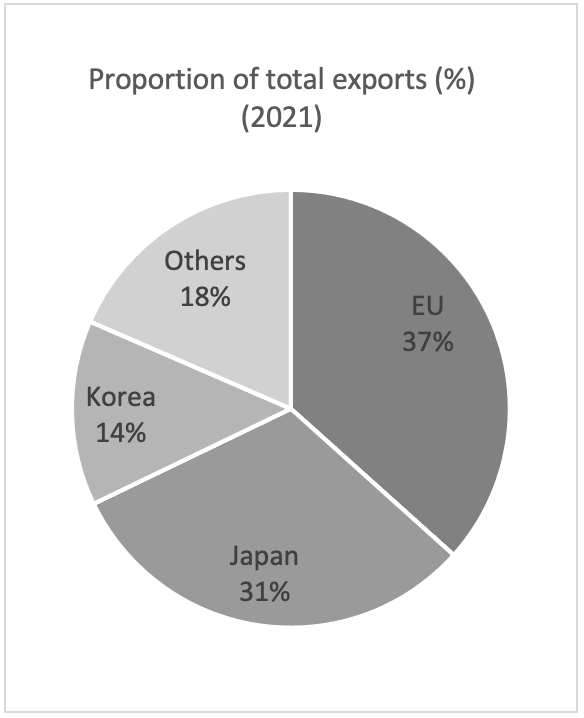

The EU as a destination market experienced the highest decline in export value (-48%) between 2019 and 2020 (see Figure 2a). Similarly, in 2019, the proportion of Myanmar garment exports to the EU compared with other markets was more than half (52%), but in 2020, it experienced a decline (-44%) (see Figure 2a). Figure 2b depicts survey data collected by the AVE (2021), which shows a further decline (-37%) in total exports to the EU in 2021. The decline in exports to the EU was further exacerbated by the military coup, which brought about a series of disruptions along the global supply chain and concerns over responsible sourcing. For example, international brands like H&M, Primark, Next, and Benetton announced they would suspend their operations in Myanmar between February and May because of the military coup and human rights concerns (Oh 2021).

Figure 2a. Proportion of total exports (2019–2020).

Source: UN ComTrade, 2021. HS code 61 and 62.

Figure 2b. Proportion of total exports (2021).

Source: AVE and MGMA (2021).

Figure 2a shows other destination markets that also experienced declines in Myanmar’s garment export value between 2019 and 2020: South Korea (-40%), Japan (-8%), and others (-4%). However, in terms of the proportion of total garment exports, the proportion of exports to Japan increased from 17 percent in 2019 to 20 percent in 2020, while the European Union (EU) dropped from 52 percent in 2019 to 44 percent in 2020. Interestingly, compared with the proportion of total exports in 2020 reported in Figure 2a, Japan’s market share of Myanmar garment exports increased, although there was a decline in export values to Japan.

It is also important to consider why the Japanese market did not decline as much as the EU. The survey conducted by the Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO) found that more than half (52.3%) of the Japanese companies stated they would continue with their operations, and 13.5 percent indicated they would expand their business. Only 6.7 percent indicated they would move their operations to another country (Japan Times 2022). These findings indicate that Japanese investors are, for the most part, committed to operating in Myanmar regardless of the double crisis. Another reason for the relative stability of garment exports to Japan is that Japanese-owned factories in Myanmar mainly export to the Japanese market.

This part of the paper has shown the impact of the double crisis on the market destinations of garment exports. Myanmar’s largest market, the EU, has experienced the greatest decline and, because of that, has the greatest effect on the sector’s growth. SMART Myanmar estimated that 60 percent of garment workers work for factories that are highly dependent on European buyers (EuroCham Myanmar 2022: 5). This demonstrates the level of business the EU generates and the impact on local garment workers, most of whom are female workers. As mentioned earlier, the EU is an integral partner, and given the reinstatement of the EU’s Generalized Scheme of Preferences, its investment has made a difference not just to the economy but also to the labor market, especially to female workers’ lives. The decline in business engagement from the EU has had a devastating impact on all strata of Myanmar society.

Factory closures, order cancellations, and production levels

The number of days a factory was closed during both crises indicates the level of disruptions that factories faced and the extent to which production was affected. It should be noted that these days of factory closures excluded public holidays and mandatory closure due to COVID-19 restrictions. Over half of the factories surveyed (62%) indicated they have closed their factories temporarily due to the crises in 2021.

As shown in Figure 3, the two townships that experienced the most factory closures (i.e., almost 40 days) between January and September 2021 were Hlaing Thayar and Shwe Pyi Thar. The most affected factories were smaller-sized ones, which experienced over 50 days of closure (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Days of factory closures.

Source: AVE and MGMA (2021).

The supply chain disruption (e.g., the closure of the China-Myanmar border and the truck drivers’ and civil servants’ participation the CDM) (RFA 2021; Frontier Myanmar 2021) and the lack of orders resulted in the closure of some factories between March and April 2021 (Min Zar Ni Lin and Ngwenya-Tshuma 2021a). Another important reason for the increase in the number of days factories were closed was the anti-military protests in Hlaing Thayar and Shwe Pyi Thar, which resulted in the military imposing martial law and curfews in these townships (Bloomberg 2021). Although the data collected in Figure 3 focuses mainly on the temporary closure of factories, it is also important to consider that some factories in Myanmar have closed permanently.

Since the military coup, the once active labor dispute resolution bodies (tripartite mechanism with government, employers, and unions) are no longer operating (Min Zar Ni Lin and Ngwenya-Tshuma 2021b). The military-run Ministry of Labor does not follow or enforce the Labor Law to protect workers’ rights. Some workers have received less than half of their daily wages for the days those factories were temporarily closed, while a significant number of workers have not received any compensation for the days of factory closure (Min Zar Ni Lin and Ngwenya-Tshuma).

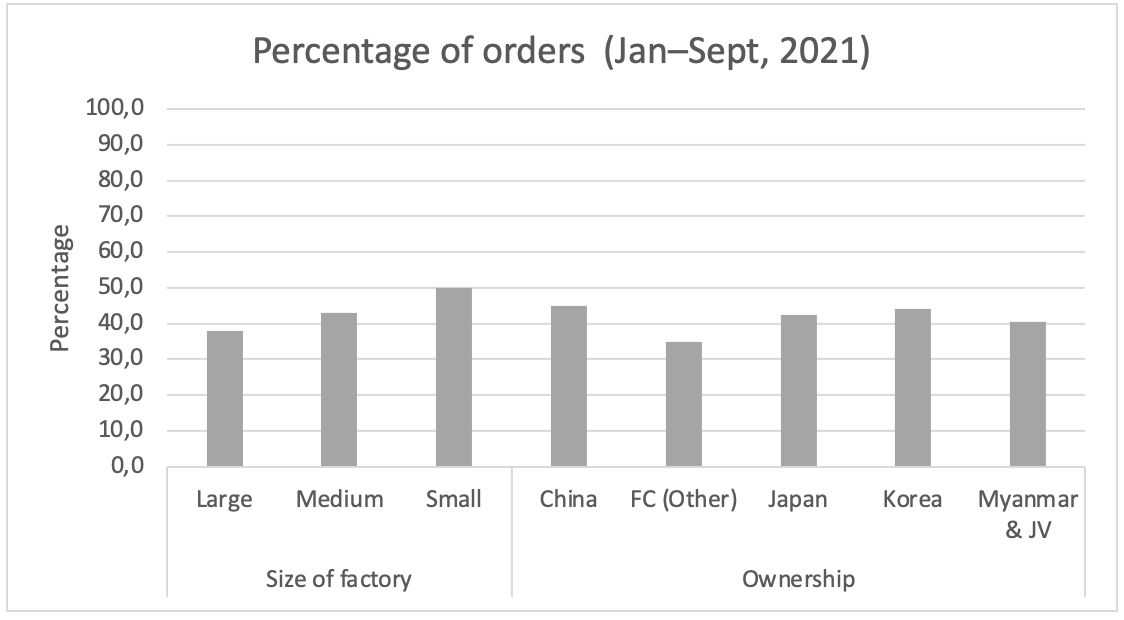

Overall, many of the factories surveyed faced a decline in orders due to the cancellation (or) suspension of orders after the military coup. Figure 4 illustrates how smaller-sized (-50%) and medium-sized (-43%) factories experienced the greatest declines in orders. Regarding ownership, the factories that faced the greatest decline were Chinese-owned (-45%) and Korean-owned (-44%). Chinese-owned factories experienced the greatest decline because they predominantly supply the EU market. With the EU market facing the greatest decline in garment exports, the Chinese-owned factories were hit hard by the decline in orders. There are three reasons for these cancellations. The first is that, during the onset of the pandemic, brands and buyers decided to either cancel orders they had already made or suspend orders for some time. Another reason was the general disruption experienced as a result of global supply chain disruptions in getting raw materials or even shipping completed orders. This was not unique to Myanmar but was experienced at a global level. Lastly, following the coup, tensions and disruptions arose in the industrial zones, which created challenges for the factories and the workers.

Figure 4. Percentage of orders by size and ownership.

Source: AVE and MGMA (2021).

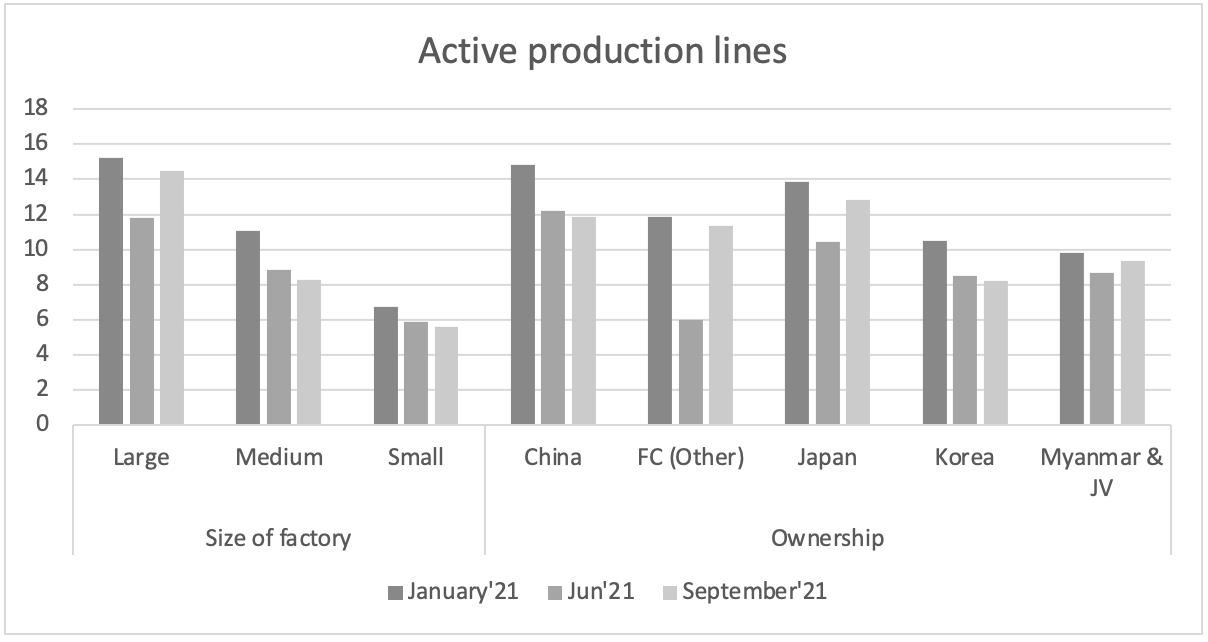

The decline in the number of working days due to factory closures, as well as the decline in orders, ultimately led to a decline in production. Figure 5 shows the number of active production lines, which is significant because the more active production lines there are in a factory, the higher the number of orders that get produced. Over three months, large factories experienced a decline in active production lines. Between January and June 2021, large factories experienced a decline in production of 20 percent. However, between June and September 2021, they saw an increase of 17 percent.

In terms of factory ownership, Figure 5 shows that Chinese-owned factories also experienced a decline of 20 percent between January and June 2021 and a further decrease of 27 percent between June and September 2021. Large-sized and Chinese-owned factories both experienced a decline of about 20 percent in active production lines between January and June 2021. However, unlike large-sized factories, Chinese- owned factories did not experience an increase in active lines between June and September 2021 compared with other investors. This is due to the continued uncertainty in orders from the EU brands and buyers. On the other hand, the concern about the rise of anti-Chinese sentiment within industrial zones after the military coup is another reason (Nikkei Asia 2021). Furthermore, like large-owned factories, Chinese-owned factories did not achieve a higher number of active production lines than when they operated before the coup. During this time, the decline in production lines is consistent with the narrative that production in the garment sector declined due to the coup.

Figure 5. Number of active production lines.

Source: AVE and MGMA (2021).

Overtime and wage expenditure

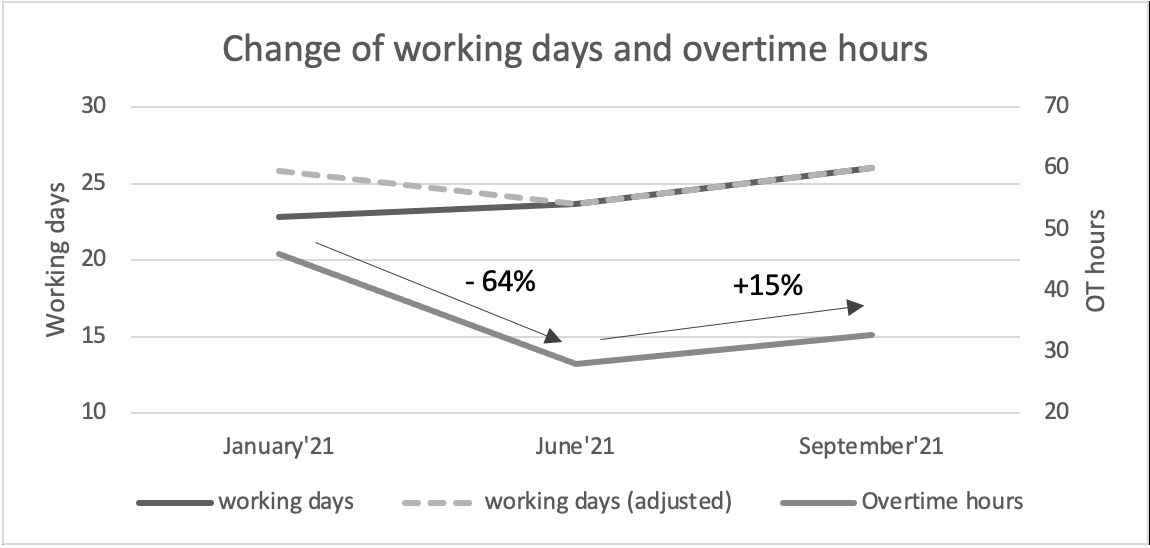

Another area that provides insight into the changes the garment sector has undergone during the double crisis is the changes in working days, workers’ overtime hours, and the wage expenditures incurred by factories. Between January and June 2021, there was a decrease in working days from 25 days to about 23 days. This can be linked to the factory closures previously shown in Figure 3. As shown in Figure 6a, there was a decline in overtime (OT) hours (-64%) between January and June 2021, and then there was a slight increase (15%) between June and September 2021. The reason for this increase could be the resumption of orders received after factories had adjusted to the new normal during COVID-19 and the wave of uncertainty after the coup.

Figure 6a. Change in working days and overtime hours.

Source: AVE and MGMA (2021).

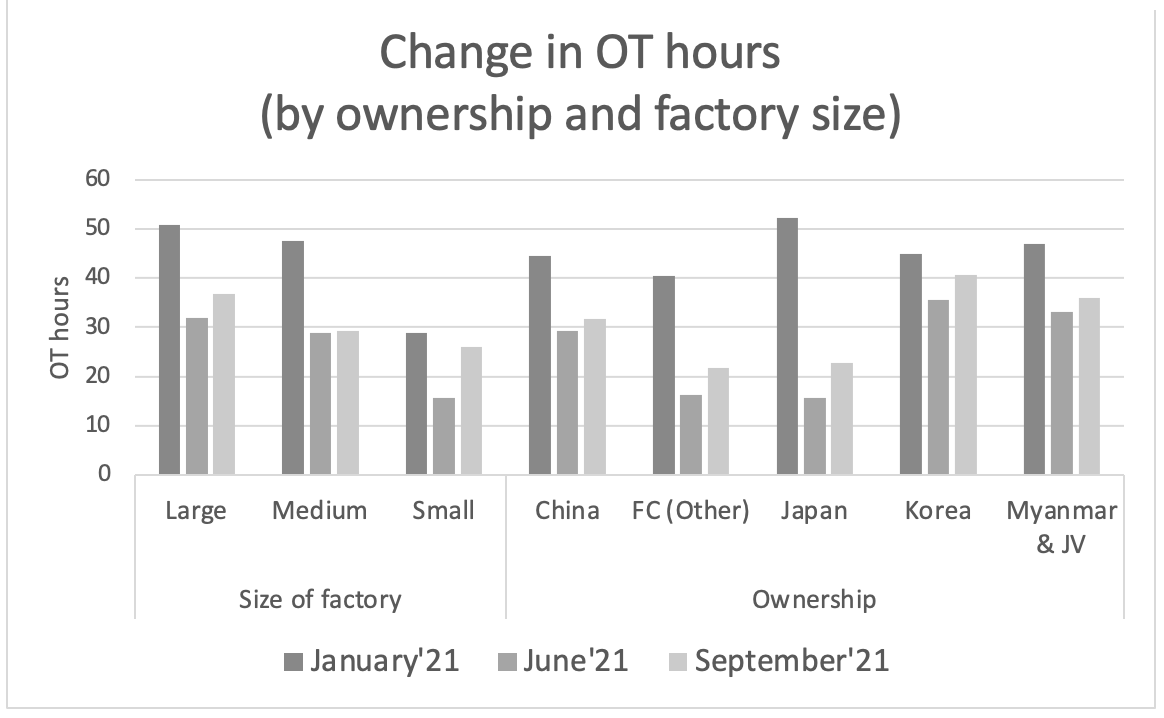

To better understand the impact of the double crisis, Figure 6b shows the change in OT hours by factory size and ownership between January and September 2021. Larger-sized factories experienced a decline (-37%) in OT hours between January and June 2021, before OT hours increased (15%) between June and September 2021, although they still did not meet January levels. Smaller-sized factories experienced a decline of almost a half (-46%) between January and June 2021 and a significant increase between June and September 2021 (67%). In terms of ownership, the Chinese-owned factories experienced a decrease (-34%) in OT hours between January and June 2021 and a slight rise (8%) between June and September 2021. Myanmar- and joint venture–owned factories’ OT hours decreased by almost a third (-30%) between January and June 2020 and increased slightly (9%) between June and September 2021.

Similar to the patterns in production levels, large (-37%), smaller-sized (-46%), Chinese-owned (-34%), and Myanmar- and joint venture–owned (-30%) factories all experienced a decline in their OT hours between January and June 2021. This is intrinsically linked to the decrease in orders and production lines, which resulted in factories not needing workers to work more hours. Furthermore, cutting workers’ OT hours is another strategy factories use to survive and continue operating. This is supported by the fact that OT hours between June and September 2021 did not increase significantly for large (15%), Chinese-owned (8%), or Myanmar- and JV-owned (9%) factories. Thus, the OT hours remained relatively low even after orders had resumed between June and September 2021. The only exception is the smaller-sized factories (67%), whose OT hours increased close back to the level before military coup. But the OT level of smaller factories was still lower compared to medium and large-sized factories.

Figure 6b. Change in OT by factory size and ownership.

Source: AVE and MGMA (2021).

OT hours are essential to garment workers because the remuneration is double the minimum wage. EuroCham Myanmar (2022: 5) also supported this, stating that “some workers are on reduced hours or furlough.”

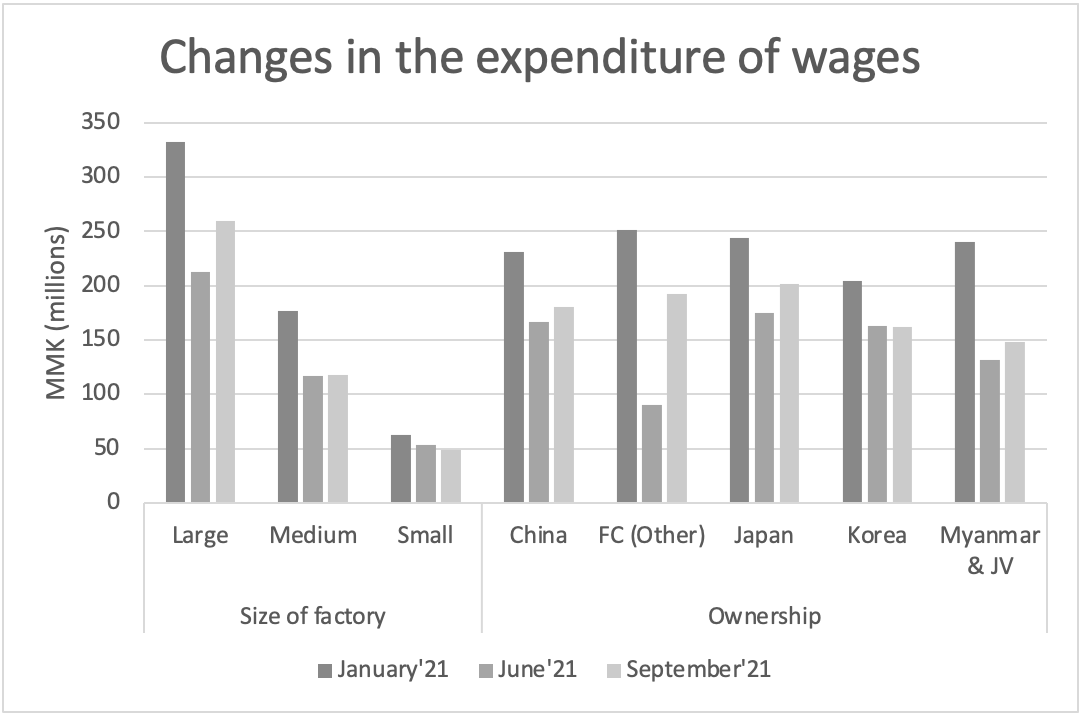

Figure 7. Changes in the expenditure on wages.

Source: AVE and MGMA (2021).

Figure 7 shows the changes in factories’ wage expenditure by factory size and ownership between January and September 2021. Larger-sized factories saw a decline in wages between January and June 2021 (-36%), and then they increased by almost a quarter (22%) between June and September 2021; however, as with production levels and OT hours, they still did not meet the January levels. Smaller-sized factories experienced a slight decline (-14%) between January and June 2021 and a slight increase (10%) between June and September 2021. Chinese-owned factories had a decline of over a quarter (-28%) in the expenditure of wages between January and June 2021 and a slight rise (8%) between June and September 2021. Myanmar- and joint venture–owned factories’ expenditure on wages decreased (-45%) between January and June 2021 and increased slightly (12%) between June and September 2021.

Myanmar no longer follows the rule of law when it comes to preserving workers’ rights. The only benefit that remains unscathed is the minimum wages workers still receive (Min Zar Ni Lin and Ngwenya-Tshuma 2021b). Before the coup, under Minimum Wage Notification 1/2018, workers were entitled to a minimum wage and OT payment but received different performance bonuses (ILO 2021: 16). Some factories have drastically decreased workers’ wages and their payments to only the minimum wage. During qualitative interviews with non-union workers, one worker explained that she could not remit any money to her family because she was not earning enough (Min Zar Ni Lin and Ngwenya-Tshuma 2021a).

Changes experienced by the workforce

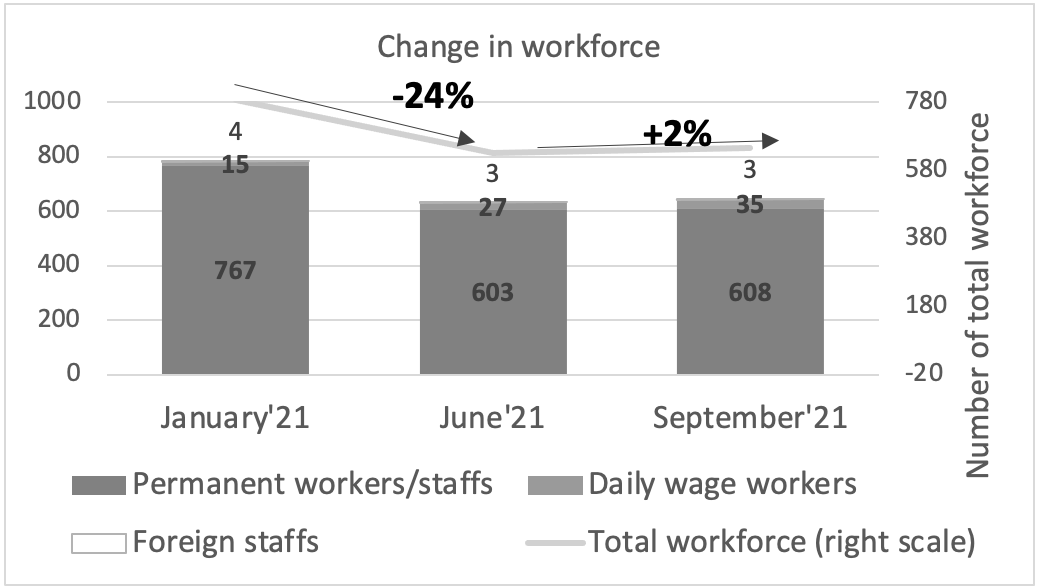

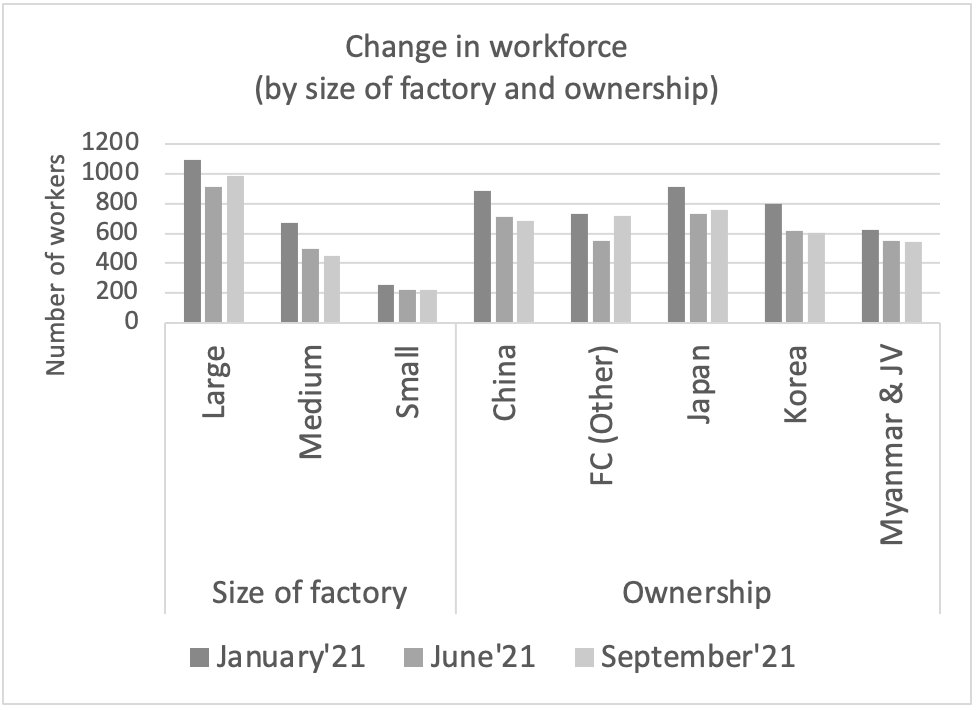

The MGMA estimates that around 60,000 garment workers lost their jobs before and a further 25,000 after the coup (Myanmar Now 2021). This study observed that between January and June 2021, there was a decline in the workforce of almost a quarter (-24%), and between June and September 2021, there was a minor increase (2%). Figure 8b shows changes in factories’ workforce by factory size and ownership between January and September 2021. Larger-sized factories experienced a decline (-17%) in their workforce between January and June 2021, and then they slightly increased (8%) between June and September 2021; however, as with production levels, OT hours, and wages, they still did not meet the January levels. Smaller-sized factories experienced a slight decline in the workforce between January and June 2021 (-12%) and a continued decrease (-2%) between June and September 2021. Chinese-owned factories experienced a decrease (-24%) in the workforce between January and June 2021 and a continued decrease (-4%) between June and September 2021.

Between January and June 2021, the data indicated a decline in active production lines (Figure 5), OT hours (Figure 6b), and wages (Figure 7). However, with the change in the workforce, there was a steady decline between January and June 2021 and between June and September 2021 for all factory types, except for a slight increase (8%) for larger-sized factories between June and September 2021.

Figure 8a. Change in workforce.

Source: AVE and MGMA (2021).

Figure 8b. Change in workforce by size and ownership.

Source: AVE and MGMA (2021).

The findings show that the garment sector experienced significant job losses during the double crisis. To survive and continue operating, factories decided to downgrade their workforce. One of their strategies after the military coup was to hire more daily wage workers instead of contracted permanent workers. As shown in Figure 9a, the number of daily wage workers increased from 15 workers in January (2% of the total workforce) to 35 workers in September (5% of the total workforce), although the total labor force declined during this period. Hiring daily wage workers is more affordable because factories do not have to pay severance payments if the work ends abruptly due to uncertainty over orders. They also do not have to provide social security and other benefits such as performance bonuses and transportation fees. This shows that some factories consider it cheaper and more economical to hire daily wage workers during these uncertain times instead of following the labor laws.

Challenges to factory operations and perspectives on the future

Despite all the challenges and the negative trends discussed in this paper, Myanmar’s garment factories are still operating. It is important to understand the factories’ greatest challenges and coping strategies to survive. The factories surveyed indicate four pertinent challenges that affected their operations (as shown in Figure 9). Firstly, most of the interviewed factories indicated that the political instability since the military coup has negatively affected their ability to do business. As previously mentioned, some international brands have been hesitant about continuing to do business with Myanmar suppliers, and some have canceled orders altogether – also because of overall security concerns. In the long term, factories will continue to face difficulties attracting international brands/suppliers if the general political and economic climate does not attract and maintain foreign investment.

The second challenge reported by the factories was access to the banking system, which has become a real problem since the coup. Within a month after the military coup, the Central Bank of Myanmar put limits on withdrawals from banks and ATMs for both individuals and companies (Ellis 2021). Given the need to access money for paying labor wages, ordering raw materials, and paying for shipping services and associated operational costs, the difficulties in the banking system make it difficult for export-oriented factories to do business.

Figure 9. Factors that have affected factories’ operations (January–September 2021).

Source: AVE and MGMA (2021).

The third challenge is the uncertainty over orders due to COVID-19 and the military coup. At the onset of the pandemic, the demand for orders declined; however, three to six months later, the orders picked up again, and factories adapted to doing business during the pandemic and ensured that their operations all complied with COVID-19 regulations. At that time, the factories employed the strategy of terminating their full-time workers and employing more daily wage workers who could help them meet their production targets and not worry about keeping them if there were no new orders (ILO 2021: 19). Given the added political instability, factories now face additional hurdles in securing new orders.

The last challenge – and the one that was cited the most by respondents (as shown in Figure 10) – was access to raw materials, which is connected to the previous point relating to the banking system and how difficult it has been to access money to purchase raw materials. However, another reason stems from the disruptions in the global value chains at the beginning of the pandemic. Most factories in Myanmar get 90 percent of their raw supplies from China, and when China first experienced lockdowns, this crippled the supply chain and affected Myanmar buyers. China also imposed restrictions on any border trade-related activities (ILO 2021: 3;6). Furthermore, during the political crisis, China has maintained its decision to keep the country’s borders closed, given the conflict has spread to border regions (Shih and Li 2021). Interestingly, a significant number of respondents shared that the third wave of COVID-19 did not badly affect their factory operations.

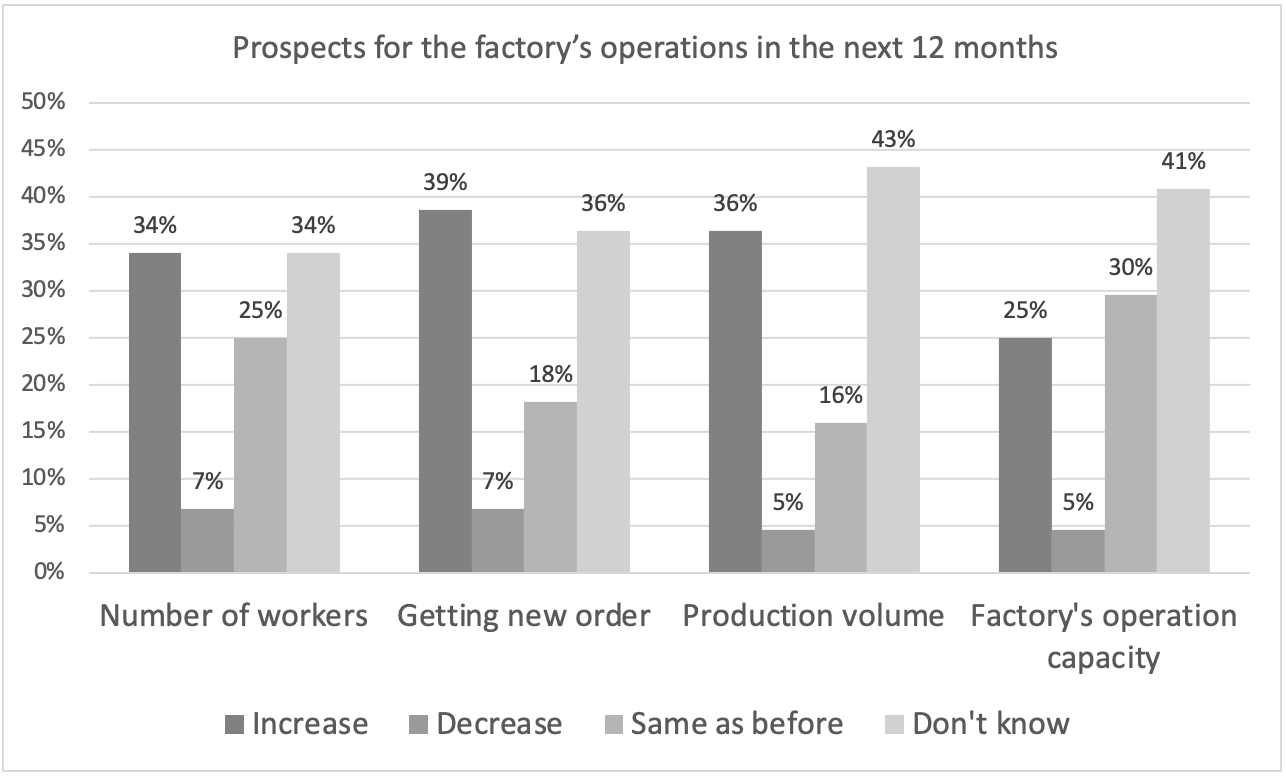

Figure 10. Prospects for the factory’s operations in the next 12 months.

Source: AVE and MGMA (2021).

Factories were asked questions about their perceptions of their future operations, as shown in Figure 10. Over a third (34%) indicated that their workforce would increase, and another 34 percent indicated they were uncertain, while a quarter indicated that the size of the workforce would remain the same. According to our findings, some factories (34%) were optimistic they would get new orders, but more factories (36%) seemed uncertain about getting new orders. Over a third of factories (36%) indicated they believed their production value would increase, but more factories (43%) were uncertain about that. The last question asked factories about their operation capacity; a quarter indicated it could increase, while more factories (41%) were uncertain about that. These findings indicate there is still a level of optimism among factory owners that Myanmar’s garment sector will prevail; however, a greater proportion of factories are uncertain about the times ahead. The garment sector has survived two crises and is still operating, which shows a level of resilience in the sector.

Conclusion

Using survey data, this paper illustrated how the double crisis in Myanmar has placed industrial development in peril – specifically, in the garment sector. In this conclusion, we will summarize some of the key findings of this paper and the implications for Myanmar’s garment sector.

Brands are facing immense pressure from international trade unions and human rights movements to withdraw (Liu and Frontier 2021). By contrast, some stakeholders, including the National Unity Government (NUG), have raised concerns about withdrawing international brands since it would have a significant impact on the well-being of hundreds of thousands of (especially female) workers, whose livelihoods and that of their families depend on their business (Myanmar Financial Service Monitor 2021). EuroCham Myanmar (2022) has stated that unethical sourcing in the garment sector and the potential to directly support the military regime is very unlikely. The aim is to build more confidence in doing business in Myanmar despite a double crisis and to preserve the well-being of the mostly female garment workers. However, since political tensions are stagnating, it is unlikely they will be resolved anytime soon, and it is hard to predict whether some EU brands will remain committed to placing orders in the medium to long term.

The data clearly shows that smaller-sized factories and Chinese-owned factories have struggled the most to recover since June 2021, as there has not been much significant positive growth in many areas. Despite the decline in the share of the EU market during the double crisis, the EU is still the largest export destination for Myanmar’s garment products. Furthermore, a drastic decline in workers’ incomes due to the double crisis threatens to drive mostly female workers and their families into abject poverty. The re-employment rate during the double crisis was also very low, and laid-off garment workers are still vulnerable.

The factories surveyed indicated four challenges to their operations, including access to the banking system, political instability, order uncertainty, and access to raw materials. Last but not least, the paper presented findings on the prospects of the garment sector, which showed some levels of optimism but also, for the most part, significant levels of uncertainty. Therefore, it will be crucial to continuously observe the changes in the garment sector and Myanmar’s industrial development to see how resilient it is and whether it will survive this double crisis in the medium term as the political tension is unlikely to be resolved in the foreseeable future.

References

- (2020), A Policy Framework for Tackling the Economic and Social Impact of the COVID-19 crisis, Policy Brief, 25 June. Available online at: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/policy-framework-tackling-economic-and-social-impact-covid-19-crisis.

- (2021b), Interview with an anonymous senior union leader in Yangon.

- (2021), “Nearly a third of garment industry jobs wiped out by coup .” Available online at: https://www.myanmar-now.org/en/news/nearly-a-third-of-garment-industry-jobs-wiped-out-by-coup.

- (2020), “Myanmar’s Economy Hit Hard by Second Wave of COVID-19: Report,” Press Release. Available online at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2020/12/15/myanmars-economy-hit-hard-by-second-wave-of-covid-19-report.

[1] Trade data retrieved from Myanmar Ministry of Commerce, cited in ILO 2021: 6.

“Arms sales can establish long-term partnerships, including technology transfer and training opportunities. They enable Middle Eastern buyers to signal foreign policy independence and diversify... Read More

“Data la loro eterogeneità, è molto difficile che i BRICS costituiscano una proposta per una visione futura della governance globale, perché il tema vero... Read More

“Chinese-backed infrastructure projects in Serbia remain a contentious issue, drawing sustained criticism from NGOs, analysts and local residents over their environmental, labor and safety... Read More

“Ovviamente la Cina sta guardando anche ad altri mercati. Proprio il 30 marzo c’è stata una trilaterale tra ministri di Cina, Giappone e Corea... Read More

“With the possibility of a U.S.-enabled Russian victory in Ukraine potentially allowing Moscow to reassert its influence in the Balkans and open a second... Read More

Copyright © 2025. Torino World Affairs Institute All rights reserved