A recent article by Jerome Alan Cohen on “A looming crisis for China’s Legal System”, which appeared on Foreign Policy, has sparked a discussion among European, American, Chinese scholars and practitioners of Chinese Law. The intellectual leadership of Jerome Alan Cohen over Western studies of Chinese law and the clear vision he has established for the field led to a passionate debate over the nexus between law and politics in China, and on what is most critical about China’s legal system.

According to Professor Larry Catà Backer from Pennsylvania State University, a nexus between politics and law is the essence of all political systems. These, in fact, are grounded on an ideology that presupposes a relationship between politics – understood also as the selection of representatives to legislative and executive offices – and lobbying, which is a means of engagement in a political process that produces law. The statement that “in China, politics continues to control the law” presupposes that China does not have a system grounded in constitutional principles that constrain political choices.

Ironically, this argument is a political in itself. Assumptions about “lawlessness” and “personal rule” are at the heart of debates about the illegitimacy of China’s legal system, arguments which tend to be the starting point of many Western analyses on China’s legal and constitutional system. In reality, that China has embraced universal values touching on legality is plain, but these values must be interpreted in accordance with the constitutional tradition of China, as China is the state where these values are embedded. In Beijing, many judges have resigned to work as lawyers, in business, or in academia. This trend can be explained by the consequences of judicial reform itself. Imposing greater risks on judges for decisions that are overturned, and a fear of continued and unlawful interference in the judicial function may explain why lawyers and judges are leaving the profession. However, arguments about Chinese law are fallacious if they assume that China’s constitutional system must be read against the template of Western constitutional systems, and if they ignore how the authority of the Party lies in the Party Constitution, and not only in the state constitution.

Jean Christopher Mittelstaedt, MA (University of Oxford) noticed how the assumption that the principal aim of a legal system is to be neutral and independent is disputable. While laudable, this assumption neglects the fundamental role that political power plays in organizing the legal system. China’s legal system does not operate in a vacuum; therefore, when analysing the legal system, it is necessary to locate its place within the Chinese polity.

Politics controls the law, but how is law understood? Traditionally, the concept of “law” (fa, 法) was not connected to the concept of “rights” (quan, 权). Law and the legal system are instruments of governance that should be judged against the stated aims of the Chinese Communist Party: the promotion of economic prosperity and social stability. Given the subordina- tion of law topolitics, the position and role of a lawyer are mediating conflicts occurring within society and protecting stability. Law is not all-powerful discipline; rather, it is on par with other political tools such as ideological education, Party building, and economic reform. Thus, the Chinese legal system must be understood holistically as inseparable from the aim of achieving a “moderately prosperous society” and the CCP’s political, ideological and organizational leadership, as outlined in the Party Constitution.

Dr. Zhu Shaoming (Pennsylvania State University, FLIA) noted that to understand why judges and lawyers are leaving the profession, we must examine the ‘quota system’. The system is part of the reform of court personnel, and is designed to ensure that the most qualified judges and prosecutors are retained, and rewarded with higher salaries. The introduction of the quota system may have discouraged younger graduates to pursue a career in justice, and increased the judges’ workload.

Yet, it is still too early to question the effectiveness of judicial reform. In the long term, a more important issue that will need to be addressed is represented by the relationship between the Party and the legal system. The governance of a state reflects the will of the Party in power, both in China and elsewhere.

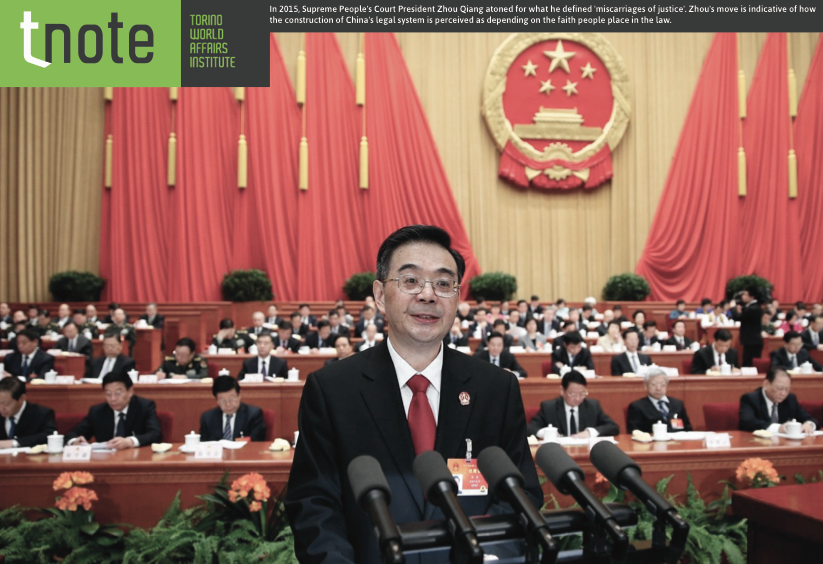

Whether China can build a predictable, reliable and independent legal system does not depend on the leadership of the Party, but on the faith people will place in the law. This is not a question of how the Party will lead judicial reform, but of how judicial, legislative, and administrative reform will work together.

Dr. Sun Yuhua (East China University of Political Science and Law) added how the goal of the quota system is to ensure that limited financial resources be used to hire highly qualified judges. Yet, an effect of this reform may be pushing younger judges out of the system. This specific reform measure may have the unintended effect of pushing young and qualified judges out of the system, while leaving less qualified judges in place. Older, less qualified judges are incorporated in the quota system ex officio, while younger judges are subject to more stringent requirements. They are required to spend at least 5 years in the position of assistant judges, but opportunities for promotions will be accessible only to 40 per cent of assistant judges. A strange phenomenon exists in Chinese courts, whereby presidents and deputy presidents of courts are bureaucrats, and do not necessarily have received formal legal education. If the quota system will keep pushing younger personnel out of the profession, then there is doubt that the prestige and efficiency of courts will be increased.

Dr. Bai Jingyu, an experienced practitioner, expressed the view the exodus of lawyers from the legal profes- sion can be explained

by two variables. First, the anti-corruption campaign launchedby the top echelons of the Chinese Communist Party is reducing the opportunities for unethical or criminal behaviour not only among party cadres, but among lawyers as well. Therefore, those unwilling to embrace and maintain high standards of ethical and professional conduct are leaving the profession. Second, the sometimes shifting trajectory of legal reform has been a cause of disillusionment among the youngest members of the legal profession who were mostly born between the late 1970s and the late 1980s. Dr. Bai further commented that perhaps the quota system is not the main reason why judges and lawyers are leaving the profession, but one of many concurring factor. The custom whereby the appointment of judges still follows a ‘seniority rule’ may be equally important.

Download

Copyright © 2024. Torino World Affairs Institute All rights reserved